source: Thomas dane Galery press release

Whose mind is it anyway?

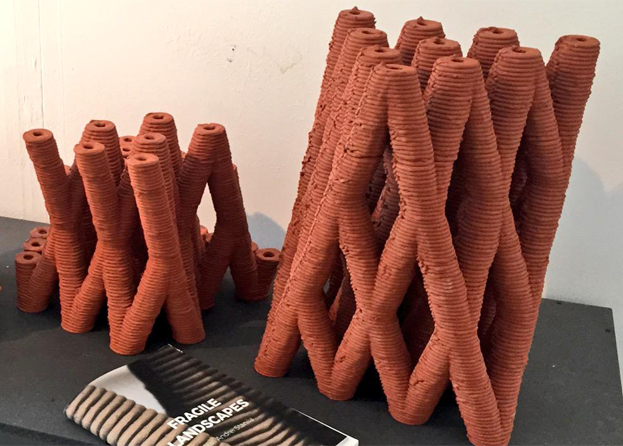

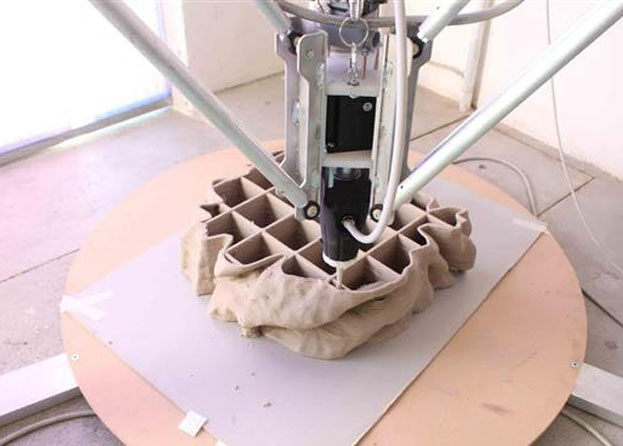

Anya Gallaccio’s ‘Beautiful Minds’ is a self-assembling artwork. Consisting of a 3D printer programmed to produce a scaled effigy of Devil’s Tower – a mountain in Wyoming – it’s a piece which dances between accident and design. Beautiful Minds rest on two conceits, and pushes its audience to consider the role of artist in relation to technology.

Whether its title refers to Gallaccio’s conceptualisation, or to the mechanism bringing it into being, the work stages the harmonious collision of nature and cutting-edge machinery. The device pipes wet coils of clay according to a precise blueprint, but the nature of the material means its assembly is anything but predictable. Soft streamers drop almost at random, and piles collapse under their own weight. The process, despite being categorically automated, results in something much closer to the natural and variable formulation of the geographical phenomenon it emulates.

Where is the artist? Beautiful Minds is necessarily without author – at least, at this late stage of its iteration. Its conception was the result of Gallaccio’s collaboration with her students from UC San Diego, a reaction to the hypertech environment of the adjacent Silicon Valley, and a natural progression of her own practice. Gallaccio’s work has spanned the organic and the man-made, manifest interchangeably in her choices of materials and structures (a stainless-steel tree at Manchester’s Whitworth, a 3D printed Sequoia stump at Contemporary Austin later this year), throughout her career. In each case, definitions of making, artistic authority and the ‘artwork’ itself are all thrown into question

![]()

Anya Gallacio’s Beautiful Minds (2015) consists of a giant 3D printer building a clay mountain

Where does assembling the work end and the work itself begin? In Beautiful Minds at Thomas Dane, the means of production are part of the product, and so is the practice itself. Behind-the-scenes is centre stage, and the line between process and processed is blurred. Where does assembling the work end and the work itself begin? Viewers are invited to see the printing in action – between 1pm and 3pm, Tuesday to Saturday until March 25th – and the model will evolve until it takes its final incarnation, and then be destroyed. A model of something as permanent and immovable as a mountain has its lifetime cut to scale accordingly; it’s only an effigy after all.

Gallaccio has created a Beautiful Mind with her own. In constructing and programming the machine, she assembled a studio hand. Has she brought forth an artist? For the time being, that’s a label we’re only happy to apply to a human being – capable of independent thought, conceptualisation and abstraction. Currently, robotics is advancing at an astounding rate. We can programme a machine to do almost anything a human can, and plenty that we can’t. They can already produce images with more detail, far more quickly, than any person – just think of the printer in your living room. Conceptually, though, art is on the opposite end of the spectrum from technology: consider science vs creativity, canvas vs circuit-boards. As the latter advances, the gap is narrowing. One day, we might visit a gallery to see a human assembling a structure as conceived by a robot. It’s not as far away as we might think.

![]()

Still, a robot cannot conceive of a task independently, or approach a new one without being programmed to do so. One day, robots might come pre-installed with artistic sensitivity and intuition, but the most progressive amongst us is a traditionalist when it comes to art. We still crave technique, labour and a soul behind the work. Plenty of artists have their pieces made by ‘artificial’ means, but Gallaccio foregrounds the mechanism whilst undermining its authority. Beautiful Minds is deliberately deconstructed. Although the technology is sophisticated, it has been rigged to produce something rudimentary. The machine, loaded with the right kind of resin, could produce a mathematically perfect effigy of anything at all without a hiccup, but art leaves room for accident. When humans make it, they do so despite – or because of – their mortality and fallibility. Our own shadows always loom large, whether in minimalist abstraction or intimate photography. What would a being who shares none of our priorities create if they could? Would they make anything at all? It’s a fascinating proposition, one which Gallaccio nods to as it bobs, just out of sight, on the horizon. One day, we might visit a gallery to see a human assembling a structure as conceived by a robot. It’s not as far away as we might think.

By Emily Watkins. ![]()

Devil’s Tower, the mountain depicted in Beautiful Minds.

Beautiful Minds is on display at Thomas Dane Gallery until March 25, 2017.